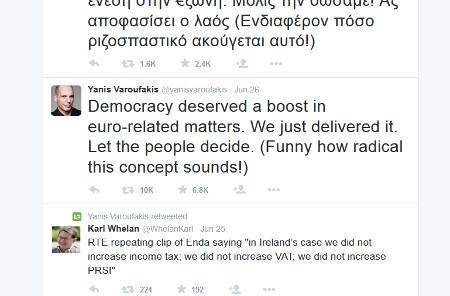

Yanis Varoufakis, the Greek finance minister, was very frank: “Democracy deserved a boost in euro-related matters. We just delivered it. Let the people decide,” he tweeted on June 26 after the announcement of his government to put the latest bailout proposals to a popular vote on July 5.

While serving a growing transnational request for more, sustainable people power in economic affairs, the offered short-cut is just another highly controversial ingredient in an unfolding Greek-European drama with global implications.

Being the undisputed cradle of ancient direct democracy, Greece has never been able to opt-in to modern forms of citizen law-making – and has instead been struggling with different types of more or less autocratic regimes involving the military, oligarchs and (most recently) populist forces on the far left and right.

The July 5 vote on two key documents by the so-called Troika (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund) offers however an insight into the challenging incompatibility between nation-state democracies and international economic governance regimes.

It is a conflict between stakeholders not being able to find a common language, which would enable them to agree on common rules, making the decision-making process free and fair. We see currently similar challenges when it comes to the controversial negotiations surrounding international free-trade agreements like the Trans-Atlantic Partnership agreement between the US and Asian countries or the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the EU and the US.

In both cases we can see huge distance between the weak (but legitimate) language used by democratic polities and the powerful (but far less legitimated) one of global businesses.

The plebiscite trap

Heading back to Greece and the upcoming “referendum” on Sunday, the proposed short-cut to what is seemingly people power by its government is however extremely problematic – for a host of reasons.

First, there is basically no institutional and cultural context in the country for such a move: the last nationwide vote on substantive issues dates back to 1974, when the Greek people had to decide how to replace the military regime: with a monarchy or a republic. They opted for the republic.

The only referendum vote which did not address an issue related to the form of government was a plebiscite on a new constitution during the military dictatorship in 1968.

However, the July 5 vote must also be seen in light of recent years of deep economic, political and democratic crisis. In October 2011 then-Prime Minister George Papandreou announced a similar move to let the people decide on an earlier bailout-agreement. While the announcement of such a referendum came as a surprise to most people inside and outside the country, Papandreou had prepared for it by adopting a referendum law earlier that year. Also, the Socialist leader proposed a three month period of public deliberation ahead of the vote. An element, which this time has been shortened to just a few days…

Secondly – and as expressed by the finance minister in the tweet mentioned above – Sunday’s vote is a highly ambivalent “boost for democracy”. The plebiscitary characteristics of this vote have been emphasised, which have little to do with a proper referendum based on a law or the process of a minority request.

Plebiscites are indeed the favourite form of “involving” the people by autocratic and populistic rulers in order to gain additional (and often instant) legitimacy. There are hundreds of such examples across the globe featuring manipulated “referendums” in history, which then again are gladly used by opponents of genuine democracy to argue against the direct involvement of citizens in the agenda-setting and decision-making process.

Typically plebiscites are based on voluntarily referrals to the people by a ruling power (president, government, parliament), the non-allowance of time and space for public deliberation (snap decisions), a problematic and biased approach to design the ballot paper and the referendum questions and – last but not least – a unclear picture when it comes to follow-up and implementation of a popular “decision”.

In Greece this Sunday, all these ingredients are part of so-called “boost for democracy”, by in fact opening all doors to further de-legitimise people power – and further strengthen extremist, populist and anti-democratic forces.

Strong ideas, weak practices

Thirdly – the Greek plebiscite-referendum offers a powerful expression of how unable (or unwilling) the European Union (and the world) still is to stick to its own core values and implement them in the political practice.

It is simply not enough to always refer to all things we do not like (war, violence, human rights abuse, autocratic behaviour etc), while not investing much more political will, resources and time to establish and develop robust and sustainable democratic infrastructures on all political levels.

Seventy years after the foundation of the United Nations (which in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights clearly established – under article 21 - the principles of modern participatory democracy) and with the EU Lisbon Treaty in place for years (also - article 11 - establishing direct citizens participation as a fundamental pillar of modern democracy), it is high time to take the proper democratic functioning more seriously – and learn from each another. This should be especially easy when it comes to referendums in Europe on Europe.

Since 1973 almost 60 such votes have been held or are about to be held in more than 25 countries. In the months to come, Denmark will organise a popular vote on reinforcing its ties to EU justice cooperation (most likely in December 2015) while the United Kingdom is lining up to a second popular vote on EU membership next year (after a first one back in 1975).

When borderless economic interests overrun and counteract fundamental democratic rights and achievements – as we experience in the current Greek-European drama – this invites all kind of forces (uninterested in modern people power themselves) to resort to simplistic, propagandist and hence deeply problematic positions.

Identifying and establishing a more sustainable balance between the internationally and nationally enshrined democratic fundamental rights and the dynamics of a free and open world is one of the key task of our generation. It is very obviously not done by a short-cut plebiscite like in Greece in this weekend, which offers more an invitation to further setbacks.

Text by Bruno Kaufmann, see original source here

Photo by Cora Pfafferott